"People who like this sort of thing will find this the sort of thing they like." (Lincoln)

| |

|

POSC 4503 Introduction to Public Policy Studies |

|

Comments on Anderson's ch 5 As always, unless otherwise noted, references to Anderson are to his 2011 7th edition assigned as a text for this course. You know the Golden Rule? He who has the gold rules. Love doesn’t make the world go ‘round. Money does. Government programs of goods and services can only be provided if there is money to pay for them, and even basic government operations (US diplomatic operations, adoption and implementation of government regulations) can only be carried out if there are funds to pay staff and maintain offices. The chapter on budgeting again illustrates the value of institutionalism (Anderson: 23-25) in understanding the policy process. Organizations (the Congressional Budget Office, the Budget Committee, the Office of Management and Budget) formal rules and procedures (the constitutional power of the veto without a line-item veto, reprogramming authority, the congressional division of budgeting among authorizing, Appropriations, and Budget committees), and informal practices (deference to Appropriations subcommittees, the bounded rationality of incremental budgeting) all matter for public policy outcomes. Budgets and political strategy

As we shall see, budgeting seriously implicates policy implementation and policy evaluation. The adequacy of budgets determine how completely programs can be implemented and budgetary stipulations can influence how they are implemented. Rising government expenditures stimulated the demands for evaluating policy effectiveness, and concerns about continued budgetary support make unfavorable program evaluations a political problem.

|

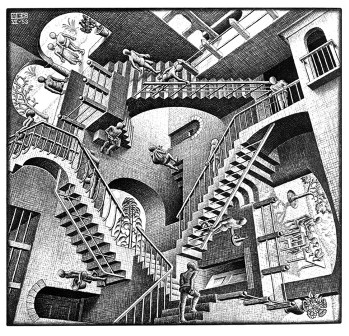

MC Escher, Relativity (1953) |